Shifting Birth Trends in Kenya

- Timothy Pesi

- May 30, 2025

- 3 min read

In Nairobi’s private hospitals, maternity wards now resemble surgical units. Soft overhead lights hum quietly, monitors beep steadily, and babies enter the world not through labour pains, but via precision incisions. In Kenya, a growing number of mothers are giving birth under the knife — and it’s becoming a costly trend.

Over the past four years, Caesarean sections have been climbing steadily, carving out a bigger share of the country's deliveries. This shift, once seen as a medical necessity, now risks becoming a default — with far-reaching consequences for the healthcare system and the insurance industry.

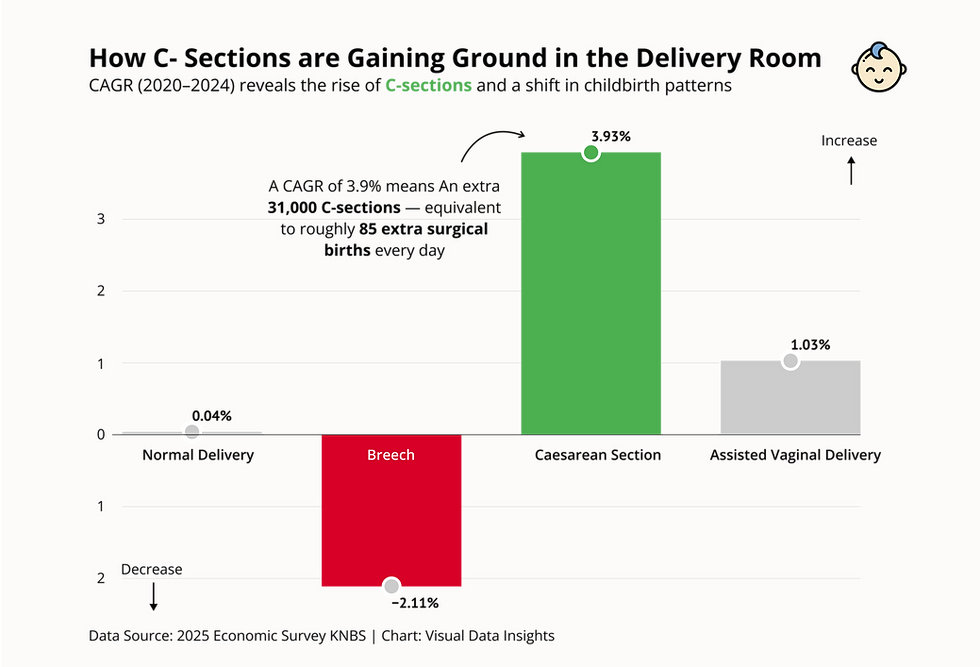

Let's chart this growth comparison:

From Last Resort to First Option

Caesarean deliveries in Kenya rose from 189,120 in 2020 to 220,505 in 2024, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.93%. That’s more than 31,000 additional surgeries in just four years. By contrast, normal deliveries — still the dominant mode — barely moved, growing by a paltry 0.04% CAGR, and breech births actually declined.

The numbers tell a story: surgery is becoming the new norm.

This is more than a medical trend — it's a financial fault line. With each Caesarean section costing between KSh 200,000 and 300,000, Kenyan's might have spent over KSh 66 billion on C-sections in 2024 alone. That’s nearly two-thirds the total cost of setting up the Social Health Authority (SHA) — a national reform meant to overhaul the entire healthcare financing system. In other words, one year of surgical births is costing nearly as much as building the system meant to pay for them.

Insurance on the Edge

Insurers are sounding quiet alarms. Once a minor cost centre, maternity claims — especially from C-sections — are now eating into profits. “We used to worry about chronic illness,” says one industry insider. “Now, it’s childbirth.”

With each procedure costing from KSh 200,000, policies built around natural deliveries are bleeding money. Some insurers are capping benefits, raising premiums, or quietly rejecting non-emergency C-sections.

Childbirth, once predictable, has become a financial fault line.

Why the C-Sections

Convenience, control, and comfort — that's the new allure of the C-section. In private hospitals, it offers a fixed date, fewer surprises, and lower legal risk for doctors. Social pressure plays a role too. In Nairobi’s leafy suburbs, surgery can signal status — a “designer delivery” that says you can afford the best. Medical necessity isn’t always the main reason. What was once a last resort is fast becoming a lifestyle choice.

The Policy Dilemma

Kenya’s Ministry of Health faces a delicate balancing act. On the one hand, expanding access to surgical deliveries has been a life-saving success, especially in emergencies. As the country rolls out its Universal Health Coverage (UHC) programme, the cost of maternal care is emerging as a pressure point. Unless addressed, it could swallow a disproportionate share of healthcare funds. Policymakers will need to draw clear clinical lines: when is a C-section necessary, and when is it not? And how should the system pay for it?

Conclusion

Kenya isn’t alone in seeing more Caesareans, but with low insurance coverage and stretched public health resources, the cost hits harder here. C-sections save lives, but when routine, they risk turning birth into a costly commodity.

In bringing life into the world, the scalpel must stay a lifesaver — not a lifestyle.

Comments