🧁 Kenya’s Growing Dependence on Wheat Imports

- May 21, 2025

- 2 min read

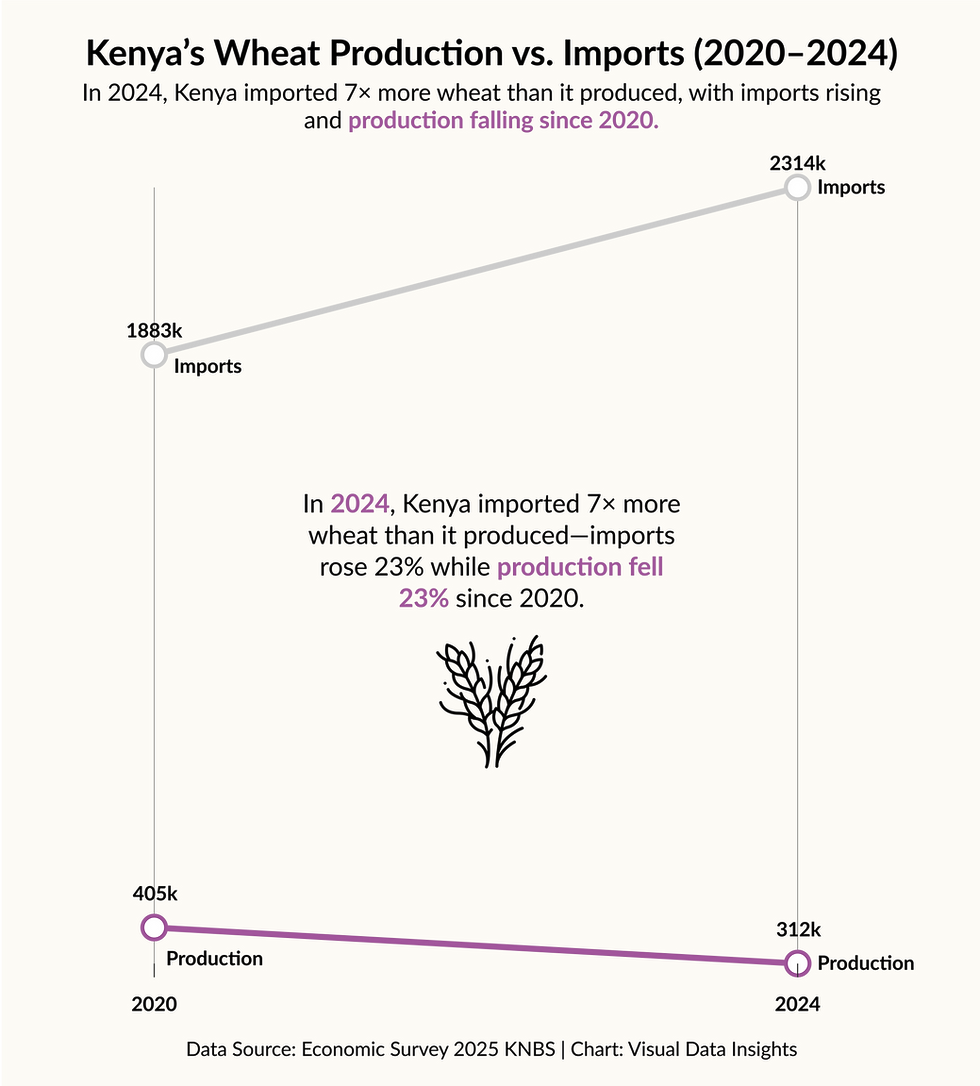

Kenya has turned the humble act of wheat farming into a spectacle of modern economic irony. The latest figures from the Economic Survey 2025 reveal a curious case: while local wheat production dawdled at 312,200 metric tonnes in 2024, imports swaggered into the national pantry at a whopping 2.3 million tonnes. That’s right — Kenya imported seven times more wheat than it produced.

Why grow when you can glow with global supply chains ? let's explore this in a chart

It appears Kenya has taken comparative advantage too literally, choosing to let other nations do the dirty business of sowing and reaping, while it perfects the art of consuming. Somewhere between climate change, policy inertia, and a national allergy to agricultural reform, wheat farming has become a nostalgic whisper of the past — something mentioned wistfully alongside rotary phones and the price of unga in 1994.

How Production Fell While Imports Ballooned

Consider this: in 2020, Kenya produced 405,000 tonnes of wheat while importing 1.88 million. Not ideal, but at least the wheat fields were still alive. Fast forward to 2024, and production has declined by 23% — now hovering just above the 300k mark — while imports have surged by 23%, hitting a record 2.3 million tonnes. It’s a perfect inverse correlation, a graph that would make any agricultural economist cry into their quinoa.

Each year, as Kenya's wheat production gently wilts like a neglected houseplant, imports gallop ahead, fueled by insatiable demand and international wheat-diplomacy. The country now operates a wheat economy akin to a teenager with a credit card: high consumption, zero production, and the assumption that someone else will foot the bill (read: the taxpayer, the importer, or possibly divine intervention).

What’s Next, Air-Imported Chapatis?

The government, ever agile in rhetoric if not results, continues to promise investments in irrigation, subsidies for farmers, and long-term strategic grain reserves. But if recent trends are any guide, it’s only a matter of time before we start importing chapatis directly, just to save on milling costs. Or perhaps we’ll outsource the entire national breakfast to India and Turkey, in exchange for some extra tea leaves and a handshake.

The truth, however satirical, is sobering: Kenya’s food security increasingly lies in the hands of ships docking at Mombasa, not farmers tilling fields in Narok. And while global trade is a wonderful thing, relying on it exclusively for your daily bread is a gamble — one bad harvest abroad, a shipping crisis, or a geopolitical kerfuffle, and the nation might find itself rationing wheat like it's 1942.

Until then, pass the butter, and pray the cargo arrives on time.

Comments